By Fred Beuttler

October 13, 2023

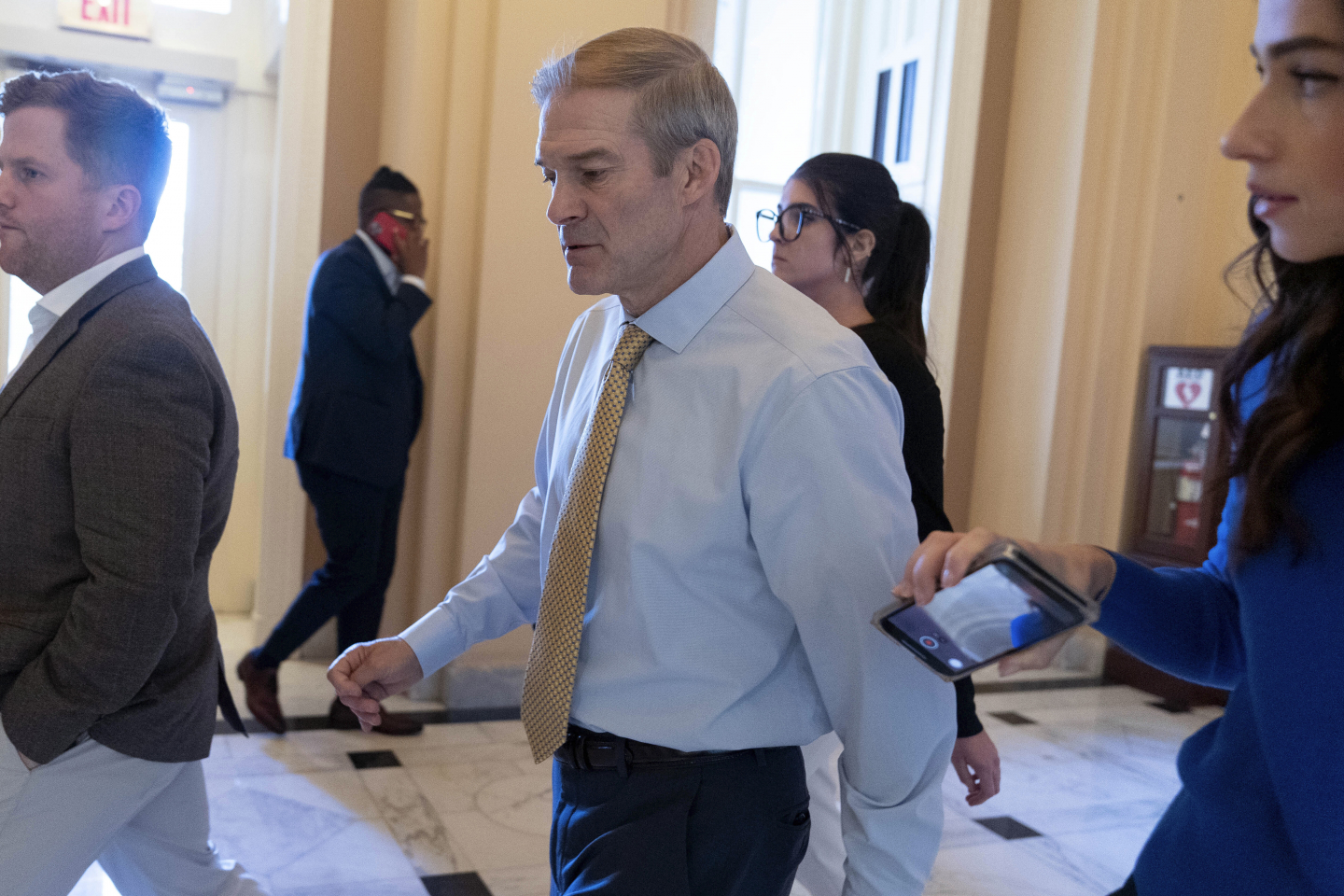

For the first time in American history, a Speaker of the House has been removed from office.

Just days prior to that historic event, a government shutdown was temporarily averted by the passage of a bipartisan continuing resolution that funds the federal government through November 17. All but one Democrat joined some Republicans in passing the CR, with a majority of Republicans opposed. Then on Tuesday, Oct. 3, Rep. Matt Gaetz made a privileged Motion to Vacate the Chair, which passed 216-210, with eight Republicans joined by all Democrats.

Now, the House will need to choose a speaker for the rest of the 118th Congress.

Does Rep. McCarthy’s removal as speaker mean that the House of Representatives, as many are saying, is “broken”? No, not as an institution. But it does reflect the stark and widening divisions that are present not only in the Republican Party but in our country as a whole.

The American founders intentionally created divided government, fearing a “party-spirit” and the tyranny of the majority. Yet they also wanted a government responsive to popular will. They based American self-government on “reflection and choice” rather than “accident and force,” as Alexander Hamilton described it in the first “Federalist” paper.

The founding fathers chose not to create a parliamentary system and instead separated power between three branches. With a weak party system, this sets up competing power arrangements, as the various branches struggle over which sets the policy agenda. Unlike a parliamentary system, in which a bare majority can pass virtually anything, our system requires agreement by three different bodies, emphasizing compromise.

The Constitution vests “all legislative power” in Congress, but it lets each house “determine the Rules of its Proceedings.” How the speaker is to be chosen is left to the House to work out on its own.

The first speakers were modeled after the British House of Commons and various colonial assemblies, where they were just neutral presiding officers. This changed in 1811 when the U.S. was divided as to which course to steer between Great Britain and Napoleon’s French Empire. In the Senate, Kentucky’s Henry Clay pushed for war with Britain over their blockade of American trade. Clay decided to run for a House seat in 1810, because he preferred the “turbulence” of the House over the “solemn stillness of the Senate.”

After the election, Clay caucused with other “War Hawks” and they elected Clay on the first ballot of the 12th Congress in 1811. Clay was not a mere presiding officer: he became a strong partisan party leader, appointing allies to chair key committees, participating in debates, enforcing House rules, and setting the legislative agenda. From that point on, the speaker was the leader of the majority party in the House.

Another powerful speaker in U.S. history was Rep. Joe Cannon, who was first elected to the speakership in November 1903. Speaker Cannon ruled the House with a firm hand, chairing the Rules Committee, which had the power to decide which bills could be debated and disciplined recalcitrant members. He also blocked much of fellow Republican President Theodore Roosevelt’s legislative agenda.

Cannon survived a motion to vacate the chair made by a coalition of Progressive Republicans and Democrats led by George Norris. But the speaker’s absolute authority was broken. Until Republicans under Newt Gingrich retook the House in the historic midterm election of 1994, power in the House shifted to committee chairmen, selected based on seniority.

Under Speaker Gingrich, Republicans adopted a rules package that started the modern trend of centralizing power back into the speaker’s office. Committee staffs were reduced, proxy voting was abolished, and committee chairs were now selected by ability and subject to term limits. Though his successor, Speaker Dennis Hastert, developed a way to choose committee chairs by a competitive process through the Steering Committee, the real power remained with the speaker. Significantly, when the Democrats returned to power under Nancy Pelosi’s leadership after the 2006 election, they retained the framework that kept power consolidated in the speakership.

What does all this history say about the House as an institution? The process is not broken. But in an almost equally divided nation, a small minority within a party can disrupt legislative operations, which often leads to that party’s defeat at the next election.

We will now see whether a House majority can coalesce behind another speaker. Until the American people make their decision in the 2024 election, and absent a rules change to increase the threshold of a motion to vacate, power will shift away from the House to the other branches. Whatever the outcome, there is little chance the House will calm its “turbulence.”

Fred Beuttler was the former Deputy Historian of the House of Representatives from 2005-2010 and was an Associate Dean at the University of Chicago’s Graham School. He is a faculty partner with the Jack Miller Center.

Share:

Related Posts

Continuing a Tradition of Civics Excellence

By Mike Sabo With new institutes emerging at colleges and universities in Florida, Ohio, Utah, Tennessee, North Carolina, Texas, and elsewhere, civics education may be

Give Me an Engaged Electorate

By John A. Ragosta On March 23rd in 1775, Patrick Henry rose at St. John’s Church in Richmond, Virginia, to urge his countrymen to arm

How Lincoln’s Assassination Changed American History

By Brian Matthew Jordan One hundred and fifty-nine years ago this Sunday, a 26-year-old white supremacist and Confederate sympathizer named John Wilkes Booth pointed a

Igniting an Appreciation for Abraham Lincoln in Children

By Jonathan W. White Historians and the general public regularly rank Abraham Lincoln as America’s greatest president. There is little doubt that he is widely