By Hans Zeiger

The field of American history is in crisis. Earlier this month, the Department of Education released troubling data indicating that only 13% of eighth-graders met proficiency standards in history. Students are failing to understand the American story and our shared values – and the consequences are severe.

To those of us in the civic education space, these scores come as no surprise. This unfortunate decline in historical knowledge has been decades in the making, starting with changes in higher education. A recent jobs report from the American Historical Association indicated a decrease in jobs across the field of history and a stark move away from tenure-track positions. Some will blame these trends on the pandemic, which certainly had devastating effects, but the erosion of history education goes back well into the last century.

Perhaps one of the reasons that history lost its footing in education is that the field has moved away from emphasizing the core texts of our national heritage.

One of the best ways to teach the complexities of the American story and human nature is through primary-source readings.

Reading primary sources gives students an opportunity to meet the engaging personalities of the historical figures who built our world. By closely examining their thoughts, students have an opportunity to understand the context of their times. Skilled teachers can even turn the study of primary sources into an empathetic quest to understand other human beings better.

Yet students today are rarely exposed to primary source material. That’s why the Jack Miller Center, where I serve as president, created ContextUS – a free, user-friendly online library and research tool of the American political tradition. The rising generation of students is immersed in technology, and that is where we need to meet them.

The platform we developed allows students (along with educators and the public) to engage with the nation’s founding documents and core texts by showing the connections and relationships between them, allowing users to uncover historical contexts throughout time. We incorporated interactive features that enable users to place texts side-by-side, add their own annotations, create study guides, and add external videos or images.

In an age of Internet misinformation, schools should not treat technology like an enemy – instead, they need to enlist it as an ally for education. So long as they are deployed to augment traditional teaching methods, innovative solutions such as ContextUS can even enhance classroom discussion. Through open exploration of historical lives and ideas taken directly from the source, teachers can humanize historical figures so that students can better relate historical ideas to the present.

Firsthand accounts of historical events can help students realize the complexity and appreciate the movement of American history.

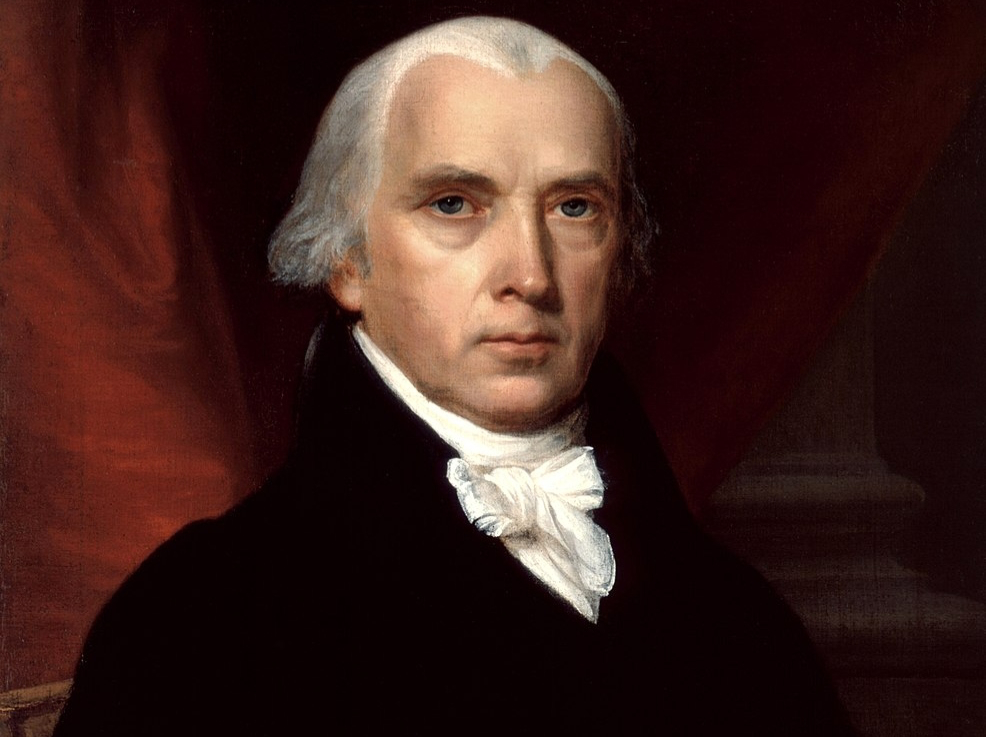

James Madison’s notes on the Constitutional Convention, for example, reveal the diversity of thought and, at times, contention within the founding generation. Though Thomas Jefferson owned slaves, his draft of the Declaration of Independence calls slavery a “cruel war against human nature itself, violating it’s most sacred rights of life and liberty in the persons of a distant people who never offended him” and a principal reason for separation from British rule. In a personal letter, Abigail Adams warns her husband John Adams to “remember the ladies” and not to “put such unlimited power into the hands of the Husbands,” cautioning that women will not be “bound by any Laws in which we have no voice, or Representation.”

Without the context and nuance such primary sources provide, history becomes vulnerable to politically driven narratives from both the left and right. We need to do everything we can to bring more Americans – educators, students, and the public alike – back to primary sources for answers.

This article was originally published by RealClearHistory and made available via RealClearWire.

Share:

Related Posts

Continuing a Tradition of Civics Excellence

By Mike Sabo With new institutes emerging at colleges and universities in Florida, Ohio, Utah, Tennessee, North Carolina, Texas, and elsewhere, civics education may be

Give Me an Engaged Electorate

By John A. Ragosta On March 23rd in 1775, Patrick Henry rose at St. John’s Church in Richmond, Virginia, to urge his countrymen to arm

How Lincoln’s Assassination Changed American History

By Brian Matthew Jordan One hundred and fifty-nine years ago this Sunday, a 26-year-old white supremacist and Confederate sympathizer named John Wilkes Booth pointed a

Igniting an Appreciation for Abraham Lincoln in Children

By Jonathan W. White Historians and the general public regularly rank Abraham Lincoln as America’s greatest president. There is little doubt that he is widely

The Patriot Week Foundation achieved its 501(c)(3) status in December 2012 and has moved forward by building a sustainable, nonpartisan organization. Currently staffed with an Operations Manager and Education Consultant, the Patriot Week Foundation will be adding to its complement of talent shortly.

This unique, historically grounded, non-partisan approach is desperately needed in our toxic political environment. In no small measure, the fate of the nation depends on it.

Get in Touch

Fill out the form, our team will get back to you ASAP.

Copyright © 2021 Patriot Week

- All Episodes

Washington Crosses the Delaware — A Christmas Tale of 1776 (re-release)

Loading...

Thanksgiving - Origins, Meanings, Traditions, and Myths (Remastered)

Loading...

Presidential Elections - The Electoral College, Origins & Development (remastered)

Loading...

Presidential Assassinations, Resignations, and Disability - the 25th Amendment Revisited

Loading...

Declaration of Independence & July 4th - Background, Recitation

Loading...

Congress: Taxes & Taxing Power (Article I, Section 8 of the Constitution)

Loading...

Memorial Day (re-release of remastered episode)

Loading...

Lexington & Concord - The Shot Heard 'Round the World (re-release)

Loading...

Congress: Enumerated Powers - The Foundation of the Constitution, Art. I, Section 8

Loading...

Congress: Lawmaking, Bicameralism, Bills & Vetoes (Article I, Section 7)

Loading...

Washington Crosses the Delaware — A Christmas Tale of 1776 (Re-Release)

Loading...

Thanksgiving - Origins, Meanings, Traditions, and Myths (Re-Release 2023)

Loading...

Congress: Taxation/Money Bills/Revenue/Origination Clause

Loading...

Congress: Congressional Immunity & Prohibition from Plurality of Office Holding (article 1, section 6 of Constitution)

Loading...

Congress - Pay, Salary, & Compensation - Constitution Article I Section 6

Loading...

Declaration of Independence - Recitation & Background (2023)

Loading...

Congressional Elections & Organization

Loading...

Memorial Day - Origins, History & Meaning (Remastered)

Loading...

Congressional Elections - Time, Place, and Manner; Meetings of Congress

Loading...

Lexington & Concord - Shot Heard 'Round the World!

Loading...

US Senate II - Elections, Qualifications, Vice President, Organization, & Impeachment Power

Loading...

George Washington - Presidents Day Episode (Remastered)

Loading...

US Senate - The Divisive & Decisive Clash over Elections, Voting & Terms

Loading...

Washington Crosses the Delaware - A Christmas Tale of 1776 (remastered)

Loading...

Thanksgiving - Thanksgiving - Origins, Meanings, Traditions, and Myths - (Remastered 2022)

Loading...

Abraham Lincoln - An Interview

Loading...

3/5 Clause & Taxes, Number of Representatives, Speaker of the House, & Impeachment - House of Representatives Part - Part 3 (Article I, Section 2)

Loading...

July 4th, 1776 & the Declaration of Independence (slightly updated)

Loading...

Memorial Day - Origins, History & Meaning (replay)

Loading...

Three Fifths Clause, Census, Apportionment, House of Representatives - Part 2 (The Constitution Article 1, Section 2)

Loading...

Congress - Two Houses & the House of Representatives - Part 1 (The Constitution Article 1, Section 1-2)

Loading...

Washington Crosses the Delaware - A Christmas Tale of 1776

Loading...

Common Defense, General Welfare & Blessings of Liberty

Loading...

A More Perfect Union, Establishing Justice, and Ensuring Domestic Tranquility

Loading...

Thanksgiving - Origins, Meanings, Traditions, and Myths

Loading...

We the People - How the Constitution's Preamble Changed Everything

Loading...

Constitutional Convention Convened - Demi-Gods Meet in Philadelphia

Loading...

The Crisis - The Unraveling of America and Rights Threatened Post-Revolution

Loading...

Articles of Confederation - Text and Remarkable Achievements

Loading...

Articles of Confederation - Drafting & Ratification

Loading...

9/11: September 11, 2001 and its aftermath 20 years later

Loading...

Signers of the Declaration of Independence - Part 5

Loading...

Signers of the Declaration of Independence - Part 4

Loading...

Thomas Jefferson's Declaration of Independence - Comparing Jefferson's draft to the final signed version

Loading...

Signers of the Declaration of Independence - Part 3

Loading...

Signers of the Declaration of Independence - Part 2

Loading...

Free & Independent States - the Declaration of Independence

Loading...

Signers of the Declaration of Independence - Part 1

Loading...

Lives, Fortunes, & Sacred Honor - The pledge of the signers of the Declaration of Independence

Loading...

Lexington & Concord - the Shot Heard 'Round the World - April 19, 1775

Loading...

Petitions Rejected - A Tyrant Revealed and the People of Great Britain Exposed as Enemies

Loading...

Slaves Revolts! American Indians, Convicts, & indentured Servants, plus Impressment

Loading...

War! Plundering Seas, Burning Towns, & Hessian Mercenaries

Loading...

Revoking Charters, Suspending Legislatures & Declaring Parliament Supreme

Loading...

Time for Revolution - When a Long Train of Abuses Invariably Evinces a Design of Absolute Despotism

Loading...

Juries suppressed, defendants shipped overseas, and the Canadian threat!

Loading...

Presidential Inaugurations - the Constitution, oaths, history, traditions, and speeches

Loading...

Impeachment Round 2 - The Extraordinary Second Impeachment of Donald Trump & the Constitution

Loading...

25th Amendment - Death, incapacity, and removal of the President and Vice President

Loading...

Taxation without representation & cutting off trade with the rest of the world

Loading...

Quartering troops, mock trials, standing armies, military superiority, & pretended Parliamentary legislation

Loading...

Immigration Halted, Justice & Judges Subverted, and Swarms of British Locusts (Remastered)

Loading...

Invasions, convulsions, dissolving and fatiguing legislatures, and halting westward expansion.

Loading...

Presidential Elections - The Electoral College, Origins & Development

Loading...

Our Enemy the King; his despotic refusal to assent to our laws

Loading...

Supreme Court Appointments - The Constitution, History, Tradition & Raw Politics

Loading...

Labor Day - Origins, Purpose & Corruption of a True American Holiday - and Beer!

Loading...

Revolution! The right to alter or abolish government.

Loading...

Limited Government, Absolute Power, & Democratic Tyranny

Loading...

The Social Compact - Key to a Just Government

Loading...

The Pursuit of Happiness - An Unalienable Right

Loading...

Liberty! An Unalienable Right

Loading...

Riots, Protests, and Mobs! An American tradition.

Loading...

Unalienable Right to Life

Loading...

Unalienable Rights

Loading...

COVID-19 Addendum: Michigan - Center of the Storm

Loading...

COVID-19 - Can they really do that?

Loading...

Equality

Loading...

Self-Evident Truths

Loading...

Nature and Nature’s God

Loading...

George Washington

Loading...

When in the course of human events

Loading...

The introductory sentence of the Declaration of Independence - “The Unanimous Declaration . . . .”

Loading...

Declaration of Independence - a full reading of the text - July 4th & Independence Day

Loading...

Impeachment! History & Today

Loading...

Welcome to our Preview Episode!

Loading...

Patriot Lessons: American History and Civics (Constitution, Declaration of Independence, etc.) (Trailer)

Loading...