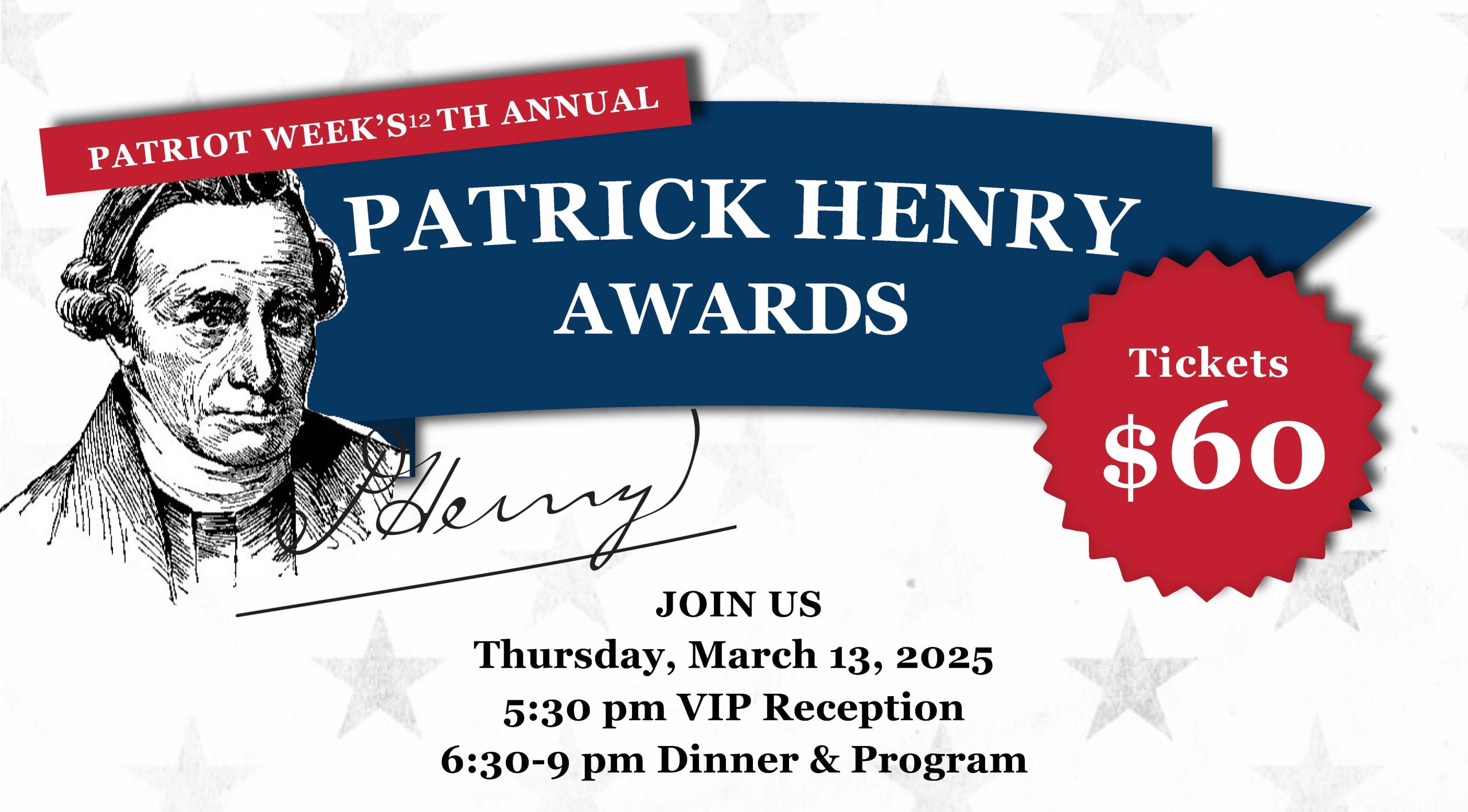

12th Annual Patrick Henry Awards & Dinner

MORE INFORMATION TO COME

By: Mike Sabo

Professors Benjamin and Jenna Storey have a motto: “Education must begin from where the students are.” Today, they note, “an increasing number of bright, politically interested young people prefer Karl Marx, Carl Schmitt, and Malcolm X to the ‘Federalist Papers,’ John Stuart Mill, and Martin Luther King, Jr.” While the Storeys find such attractions “obviously troubling,” they also “take them seriously as a sign of students’ desire to look everywhere for insight into our current political problems.”

“Like Henry Adams, intelligent young people are looking for real education,” they argue. “They want to know not only about government but also about questions of God and the good life that Plato thought were embedded in arguments about justice.”

Students can explore these enduring arguments in the Tocqueville Program, which the Storeys co-direct at Furman University. The program, they say, offers “an intellectual community dedicated to exploring the moral and philosophic questions at the heart of political life.” Located at South Carolina’s oldest private institution of higher learning in Greenville, the program launched in 2008 with the help of the Storeys’ colleague Aristide Tessitore.

Named after the French observer of early American democracy, the program invites students to take part in the great conversations that philosophers, historians, and statesmen have been having for millennia. The Storeys note that students will think about and debate “the good, the true, and the beautiful – the principles of choice that orient human life.”

A key focus is fostering in students a deep “appreciation of self-government as an activity with its own intrinsic dignity.” Students should not only be able “to tolerate the different opinions of their fellow citizens, but also genuinely to listen to those opinions, in hopes of further clarifying the grounds of their own ways of life.” The Storeys work to prepare students “to make good use of the freedom and social peace our political order affords us.” They argue that the “active efforts of citizens, rather than passive acquiescence or the exclusive defense of individual rights,” is necessary for republican government to function well.

The Storeys argue that these responsibilities require “civic education to a peculiarly high degree,” because “our republican political order asks a lot of a person, including many things that do not come naturally.” Through its classes, activities, and fellowships, the program promotes a “civic education that seeks to meet the needs of our moment.” It prepares students to “understand how politics can be part of the quest to live well,” they continue, “while also protecting the familial, religious, business, civic, and educational institutions that have their own distinctive place in that quest.”

A yearly lecture series features scholars and intellectuals such as Yuval Levin, Cornel West, Patrick Deneen, Martha Nussbaum, Diana Schaub, and Jean Yarbrough speaking on crucial themes such as the crisis of liberalism and the nature of the American republic.

The Society of Tocqueville Fellows is made up of a select group of undergraduates who study the American and Western philosophical traditions and take part in extracurricular discussions during evening seminars and weekend retreats. Those looking to dive deeper are welcomed to join the Political Thought Club, which meets each Friday during the school year. Students read and discuss selected texts from notable philosophers, scientists, and statesmen such as Blaise Pascal, Ibn Tufail, Charles Darwin, Edmund Burke, Alexander Solzhenitsyn, and, of course, Alexis de Tocqueville himself.

Freshmen are welcomed to participate in the Engaged Living Program, in which a group of students live and learn together. They take a two-semester course, taught by the Storeys, that guides them through “questions of justice, the good life, and the best regime with the help of Plato, Aristotle, Thomas Aquinas, Machiavelli, Locke, Tocqueville, and Martin Luther King, Jr.” Their aim, the Storeys say, is to “encourage students to bring their social lives and intellectual lives together, so that they experience the friendship that can be found through ‘shared thoughts and speeches’” – relationships Aristotle once described “as the deepest form of human community.”

The Storeys note that a well-grounded civic education requires carefully reading old books and taking classes from teachers who appreciate the wisdom of these texts. “The work of an older generation is not to scold or radicalize the young, but to help the young find the education they are looking for – sometimes without knowing it.” They urge students to “read every text as if it might contain priceless wisdom that could reorient a life.”

The Storeys see their job as being “faithful stewards of the texts we teach, and to pass that spirit on to our students and the young scholars who work with us. It seems to us that there is nothing more important for the revival of American civic education.”

Mike Sabo is the editor of RealClear’s American Civics portal.

MORE INFORMATION TO COME

By Mike Sabo With new institutes emerging at colleges and universities in Florida, Ohio, Utah, Tennessee, North Carolina, Texas, and elsewhere, civics education may be

By John A. Ragosta On March 23rd in 1775, Patrick Henry rose at St. John’s Church in Richmond, Virginia, to urge his countrymen to arm

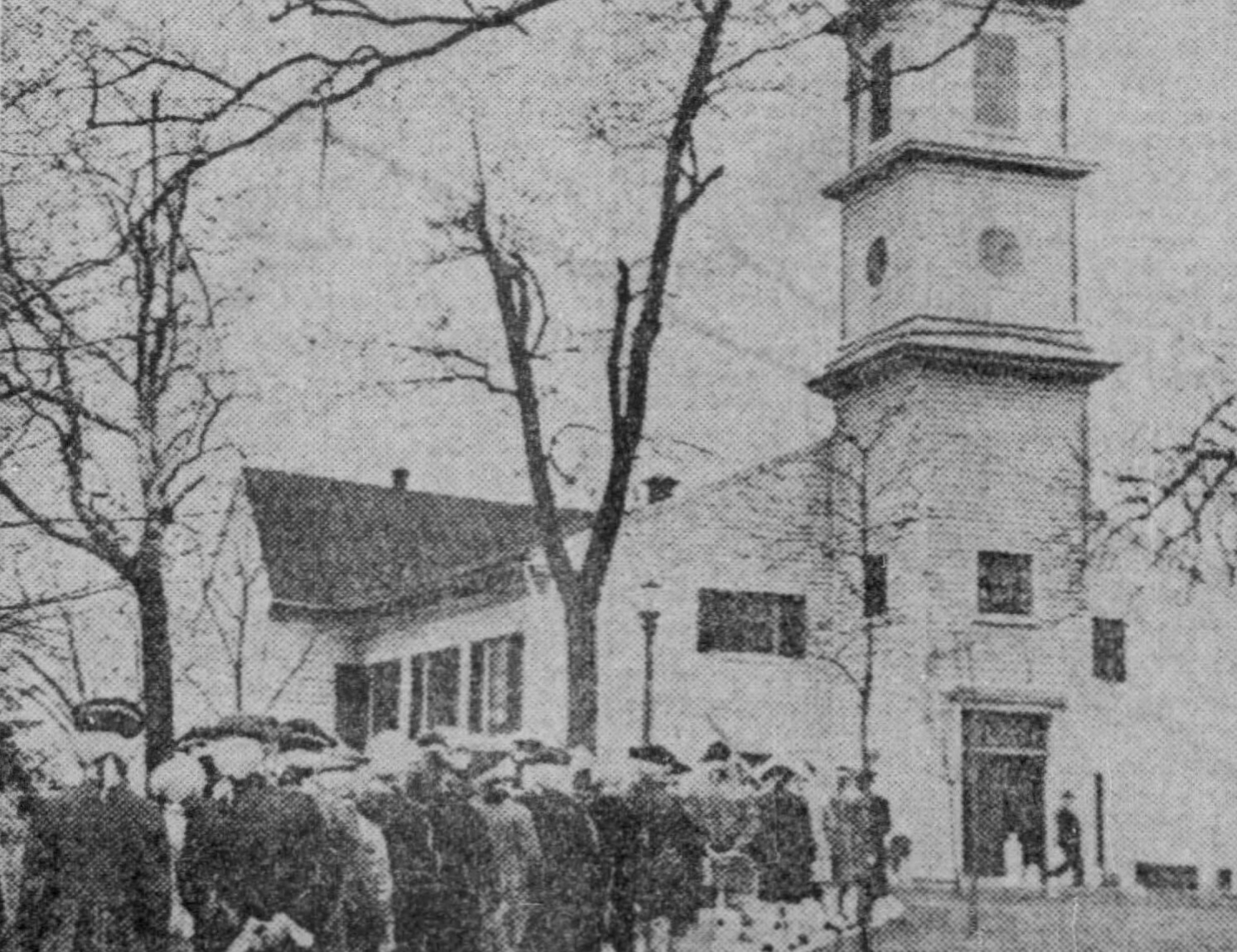

By Brian Matthew Jordan One hundred and fifty-nine years ago this Sunday, a 26-year-old white supremacist and Confederate sympathizer named John Wilkes Booth pointed a

By Jonathan W. White Historians and the general public regularly rank Abraham Lincoln as America’s greatest president. There is little doubt that he is widely

The Patriot Week Foundation achieved its 501(c)(3) status in December 2012 and has moved forward by building a sustainable, nonpartisan organization. Currently staffed with an Operations Manager and Education Consultant, the Patriot Week Foundation will be adding to its complement of talent shortly.

This unique, historically grounded, non-partisan approach is desperately needed in our toxic political environment. In no small measure, the fate of the nation depends on it.

Get in Touch

Fill out the form, our team will get back to you ASAP.