Continuing a Tradition of Civics Excellence

By Mike Sabo With new institutes emerging at colleges and universities in Florida, Ohio, Utah, Tennessee, North Carolina, Texas, and elsewhere, civics education may be

THE 1776 SERIES

By: Steven B. Smith

This is not to say that patriotism in on the verge of disappearance, but it has come to seem ethically challenged in today’s cancel culture. Yet once you leave any urban environment, it is not hard to find people with no reservations about their love of country who are willing to express it on bumper stickers on cars or trucks, in bars and diners, and in houses of worship. The problem is that the country they profess to love is often at odds with what many of us would find welcoming. It is often insular, exclusionary, and intolerant. Given this dilemma, what is a liberal and a patriot like myself to do? This was the dilemma in which I found myself when I decided to write my book Reclaiming Patriotism in an Age of Extremes. I must admit that one of the secret pleasures I had in writing this book was looking at the expressions of shock, horror, and occasionally disgust on the faces of colleagues when they found out I was actually planning on defending patriotism.

Patriotism has always been a contested virtue because it must contend with other loyalties – to family, friends, tribe, and religion.

Patriotism has always been a contested virtue because it must contend with other loyalties – to family, friends, tribe, and religion. As any reader of Sophocles’ Antigone would immediately recognize, the conflict between loyalty to family and loyalty to state is as old as Western literature. In the case of virtually inevitable conflicts of loyalties, it is not clear which side has priority. Modern patriotism must contend with two alternatives that vie for predominance: nationalism and multiculturalism.

On the right, patriotism must be distinguished from nationalism. Nationalism and patriotism initially grow out of a legitimate desire for self-determination, but over time nationalism has morphed into an ideology of grievance and resentment. It has become a weapon for determining who is in and who is out, who is a real American and who is not. Nationalist stories are typically narratives of treason and betrayal by unscrupulous elites, in which listeners are encouraged to feel contempt for fellow citizens who fall outside the dominant ethnic group. Nationalists seek the warmth of community but usually at the expense of an out-group that is deemed un-American, regarded as traitors and enemies of the people. Nationalism thrives on the oppositional language of “friend” and “enemy” and is impossible without it.

On the left, the critique of patriotism is undertaken by multiculturalism and “identity politics.” Multiculturalism was originally an academic theory that sought to give voice to previously underrepresented minorities – women, African-Americans, gays – but over time has evolved into a race for victim status and a far-ranging critique of American history. Critical Race Theory, endorsed by the 1619 Project, dates the American founding from the time when twenty African slaves were sold to the Jamestown Colony in Virginia. On this account, American history – even the American Revolution – is based upon persistent racial oppression and white supremacy. Although these claims have been widely repudiated by some of our best historians, they continue to gain traction in public schools and universities. Such views are based on a radical simplification and reduction of all of American history to a single theme.

From America’s beginnings, then, slavery was a great moral conflict; to pretend that a defense of white supremacy is the one constant running throughout our history is not true to the facts of our national experience.

The truth is more complicated – that even at the time of the American Founding, the institution of slavery was highly contested. The original version of the Declaration of Independence included a pointed denunciation of slavery as a practice incompatible with the rights of man. Benjamin Franklin and Alexander Hamilton headed abolitionist societies in Pennsylvania and New York. Even the founders who owned slaves believed the institution was gravely wrong. George Washington freed all his slaves (and provided for their future education and provision) in his final Will and Testament. From America’s beginnings, then, slavery was a great moral conflict; to pretend that a defense of white supremacy is the one constant running throughout our history is not true to the facts of our national experience. One reason I cannot accept this view of America as a white supremacist nation is that it denies the efforts of generations of Americans – black and white – in their struggle to achieve a more perfect union. Slavery is an irreparable stain on America, but it is not the essence of America.

So how does patriotism differ?

Patriotism is, above all, a form of love or loyalty. We admire loyalty to family, friends, sports teams, even institutions – up to a point. Yet loyalty also sits uneasily with other qualities that we equally admire – fairness, justice, mercy, equality, and open-mindedness. These do not always sit easily together. There seems something primitive, almost primordial, about loyalty, almost like the Mafia code of omertà.

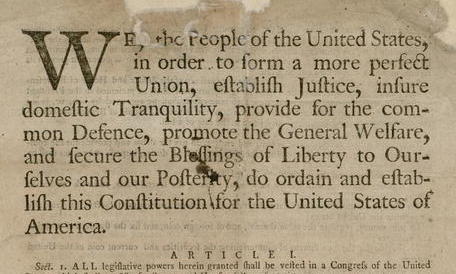

Patriotism is ultimately a form of constitutional loyalty. It is not simply loyalty to the people of the United States but loyalty to a particular constitutional order, what we call a liberal democracy or a constitutional democracy. Our Pledge of Allegiance is an oath to the flag “and the republic for which it stands.” This commitment stakes a claim. American patriotism is not based on loyalty to blood and soil but to a form of government – a republic or a democracy as we would call it today. Ours is a uniquely constitutional patriotism. A change of constitution – not just a change of administrations – would require a change of loyalty.

Patriotism is ultimately a form of constitutional loyalty. It is not simply loyalty to the people of the United States but loyalty to a particular constitutional order, what we call a liberal democracy or a constitutional democracy.

American patriotism is uniquely a patriotism of ideas. We are and have been from our beginnings a people of the book (or books). The Puritans thought of themselves as creating a “city on a hill” – a new Jerusalem in the wilderness of New England. This is why the Hebrew urim v’tumin (somewhat ludicrously translated as Light and Truth) is on the seal of my university. The American Constitution’s framers followed in their footsteps, attempting to create a text that would stand the test of time. From the beginning, ours has been a patriotism of ideas, and no idea was more important than the idea of equality given voice in the Declaration of Independence – and no one has put greater emphasis on this concept than our greatest patriot, Abraham Lincoln.

But loyalty to a constitutional order is not only a matter of the head but of the heart. It is not only a matter of logos but of ethos. An ethos is not just a manner of thinking but of feeling, of both sense and sensibility. The concept of ethos is an ancient one. It comes from the Greek word for habit or character. “The ethos of a man is his destiny,” the pre-Socratic philosopher Heraclitus remarked, suggesting that character is fate.

The idea of ethos patriotism runs into an evident difficulty. Doesn’t loyalty to one country or way of life stand in contradiction with the principles of equality and moral inclusiveness that are equally part of American patriotism? How can I regard all persons as equal if my loyalties are to my country alone? Where is the line drawn between what we owe to fellow citizens and what we owe to fellow human beings who may be experiencing pain and suffering? Some version of this question is at the core of our current debates about border security and immigration. Are we at bottom a nation of immigrants who welcome the stranger – “your huddled masses yearning to breathe free,” in Emma Lazarus’s phrase – or do we require a border wall as a way of protecting our national sovereignty? How broadly or narrowly do we draw the line? In defining ourselves too broadly, we risk losing our ethos; in defining ourselves too narrowly, we risk losing our humanity.

Another fear is that ethos patriotism leads us to ignore past and present injustices, resulting in a kind of blind faith. This is a legitimate concern, but patriotism, as I understand it, can be critical and self-correcting. Consider the case of Congressional Medal of Honor winners who had previously been overlooked due to their race. What is this but an expression of regret for our previous failures and a desire to enlarge on who is considered part of the American family? No one ever doubted Ronald Reagan’s patriotism, yet he apologized to Japanese-Americans for their internment during World War II.

Patriotism is not the same thing as a simple “my country right or wrong.” It is a desire to see one’s country live up to its highest promises.

Patriotism is not the same thing as a simple “my country right or wrong.” It is a desire to see one’s country live up to its highest promises. This was the idea behind Martin Luther King’s “Letter from a Birmingham Jail,” in which King appealed to the country to live up to its founding principles. Like Lincoln before him, he appealed to the Declaration of Independence as America’s mission statement and pole star. Even while protesting southern segregation statutes, King did not lose faith in America and its progressive aspirations. King’s act of simple and dignified resistance shows that patriotism can indeed be combined with self-criticism.

Consider Lincoln’s description of Americans as an “almost chosen people,” the term “almost” suggesting that there is more work to be done. Lincoln and King appealed to what was best in our traditions, not to what is worst. Critique is best exercised when it grows not out of detachment and resentment but out of care and love. This is an example from which many of today’s social justice activists might take a lesson.

Things were not always this way. Colleges and universities were once considered the custodians of our most important civic values. Fields like history, political science, and literature were thought to prepare one for a life of national service. Patriotism was not indoctrination into an ideology but an essential component of an educated mind. The proper love of country is not something we inherit; it must be taught. The proper love of country belonged to a literary tradition that might include the great patriotic speech in Shakespeare’s Richard II (“This blessed plot, this earth, this realm, this England”), but in an American context would certainly include works like Benjamin Franklin’s Autobiography, Ralph Waldo Emerson’s “Self-Reliance,” Lincoln’s “Gettysburg Address,” and F. Scott Fitzgerald’s The Great Gatsby, all of which taught generations of students what it means to be an American. Today we would add the works of Frederick Douglass, James Baldwin, and Toni Morrison.

Patriotism was not indoctrination into an ideology but an essential component of an educated mind. The proper love of country is not something we inherit; it must be taught.

Today it is necessary to recapture patriotism from two contending dispositions. Those on the left have largely ignored patriotism when they have not been openly contemptuous of it. They view any expression of national loyalty as synonymous with racism and white supremacy. But if patriotism must be rehabilitated for those on the left, it must also be recaptured from those on the right. For some on the right, love of country is too often used as a cudgel to separate and divide the ins from the outs. Among the new nationalists are people who see themselves at war with relativism, multiculturalism, and identity politics that they view as posing an existential threat to American national character. The language of fear, invasion, and impurity remains a staple of this rhetoric. Whatever may be the sins of multiculturalists, they are not enemies of the state. We were at war in Germany, Japan, Korea, Vietnam, and Iraq. We are not at war with other Americans over their claims to cultural identity. This language of culture war has turned patriotism into a game of “capture the flag,” where each side expresses feigned outrage at the moral idiocies of the other.

Both these extremes are dehumanizing – and they are mirror images of one another. If patriotism misused can be harsh and punitive, at its best it can be elevating and ennobling. It would be easy, as we witness the rise of ethno-nationalism in some parts of the world, to reject patriotism as tainted with xenophobia, racism, and other forms of ethnic and religious bigotry. But things are not so simple. These are not expressions of patriotism but perversions of it. Patriotism is frequently equated with making sacrifices for one’s country during times of war and in the extreme case, the sacrifice of life itself. This is true on such dramatic occasions, but more often patriotism involves small sacrifices like wearing a mask or getting a vaccine to contain a raging pandemic – not just for yourself but for the health and safety of your family, friends, and neighbors. If these demands seem too much to ask, if they seem to violate your inviolable right to liberty, then you will likely be incapable of any greater sacrifice for the public good when it is required.

Steven B. Smith is the Alfred Cowles Professor of Political Science at Yale University. He has written or edited books on Hegel, Spinoza, Lincoln, Leo Strauss, and Isaiah Berlin. His most recent book Reclaiming Patriotism in an Age of Extremes was published by Yale University Press earlier this year. He is currently working on a book titled Why Lincoln Matters.

By Mike Sabo With new institutes emerging at colleges and universities in Florida, Ohio, Utah, Tennessee, North Carolina, Texas, and elsewhere, civics education may be

By John A. Ragosta On March 23rd in 1775, Patrick Henry rose at St. John’s Church in Richmond, Virginia, to urge his countrymen to arm

By Brian Matthew Jordan One hundred and fifty-nine years ago this Sunday, a 26-year-old white supremacist and Confederate sympathizer named John Wilkes Booth pointed a

By Jonathan W. White Historians and the general public regularly rank Abraham Lincoln as America’s greatest president. There is little doubt that he is widely

By Hans Zeiger December 15th marks Bill of Rights Day, which commemorates the 232nd anniversary when the first ten amendments to the U.S. Constitution were